Hamlet, Shakespeare’s longest play, ventures into the themes of doubt, truth, fate, meaning, and the slipperiness of reality. Set in the corrupt Kingdom of Denmark, the play dramatizes the revenge Prince Hamlet exacts on his uncle Claudius for murdering King Hamlet, Claudius’ brother and Prince Hamlet’s father, and then succeeding to the throne and taking Prince Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, as his new wife and Queen.

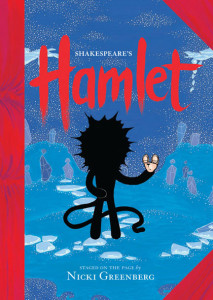

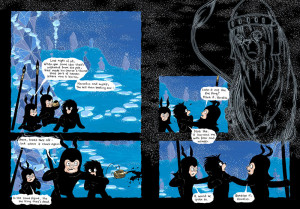

In Nicki Greenberg’s graphic novel adaptation of Hamlet, the page layouts are based around the idea of a theatre stage, with full-on interlocking sets that echo the tone of the current scene. Each character is an inkblot with an interchangeable and removable mask. Greenberg incorporates the black space around the graphic frames as part of the novel to great effect; we are invited into the dark backstage of the play and allowed peek around the corner into a world we don’t deserve to see.

Greenberg, an Australian writer and illustrator, previously adapted F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby into a graphic novel (which, after reading her Hamlet, I immediately sought out and purchased). Gatsby is presented as a sepia photo album of sorts, with each photo conveying a few lines of dialogue or narration. Hamlet, on the other hand, is in full colour and is not confined to the borders of such a format. Instead, it plays with the borders themselves and takes full advantage of that experimentation.

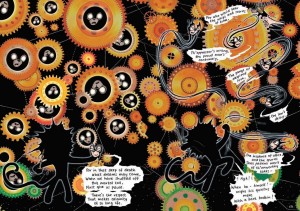

Each page is a work of art, from the starlit spookiness of the first ghost scene to the terrible, monochromatic carnage of the final battle. The flower-strewn pages of Ophelia’s madness, the colourful cog-churning interiors of the castle, Gertrude’s gauzy pink bedchamber, the sickly green rooms where Claudius plots and conspires, and the play-within-the-play are all in brilliant, sun-bright colour, and open up the flourishing world to its full extent.

At the end of each scene, we are presented with a chilling tableau of parallel events occurring behind the scenes of the novel itself. It’s bewilderingly clever, and at the end of the book the two realities collide in a surprising twist. Plays within plays within plays invite us to return to one of Hamlet’s fundamental questions: which side of the stage is real?

The characters are moldable like clay – they stretch, splatter, melt, fuse together and assume strange and monstrous forms, which is delicious to lick up as a reader. The bodies of the characters/actors in the story are lifelike and engaging as they move about the page. Greenberg’s Hamlet is not a generically delicate study in melancholy, as he has been portrayed countless times, but leans more toward the muscular, playful, dangerous and charismatic. We are welcomed into a side of him that’s charming, damaged, tender in friendship and full-hearted in his all of his vices. Hamlet is a deliberately mysterious and ambiguous creature, and seeing him treated with care instead of shredded into fragments for analysis was refreshing.

Instead of using the intimacies of real theatre, Greenberg delves into a different type of toolbox in terms of how she conveys the characters’ emotions. She exploits the shape and layout of the page and the panels within it, the visual echoes and resonances of composition, different ways of timing the performance (such as the impact of the page-turn, which she goes into, among other elements of the novel, in surprising clarity in her interview about the novel), speech bubbles, and the ability of the graphic novel medium to bend the laws of biology and physics.

The painted backgrounds and larger-than-life botanical ‘props’ also play a large role in the storytelling. The eight backgrounds, representing eight different locations in the castle of Elsinore, are designed to operate as surreal theatre sets, where perspective is fluid and ambiguous. The sets themselves can twist and fracture, grow eyes, breathe out ghosts and meld with their inky surrounds. The backstage sets, on the other hand, are collages constructed from old books, frayed ribbons, handmade paper, Folies Bergère albums from the 1920s and 30s, peacock feathers, silk scarves, old boxes and bottles of ink, nibs, dyes, labels, sequins etc. This gives a sense of bringing our imaginations back to a clothy reality after the twists and turns of the previous scene, and gives us reading glasses with different coloured lenses with which to use when poring over the split world of Hamlet.

The ‘to be, or not to be’ soliloquy – perhaps the most famous piece of dramatic speech in history – would have clearly been a challenge for Greenberg, but yet again she takes the play to a whole new level. It is at this point in the play where Hamlet removes his own face and strikes up a conversation with it as it taunts him from the end of his outstretched arm.

For people unfamiliar with Shakespeare’s work, the text can be intimidating when encountered in great blocks, or even when spoken quickly on stage or screen. This novel, however, is a delight and can be explored and enjoyed with young children (especially those looking to discover new words) as well as adults, and provides an insight into the work of a great cultural icon of the English language.